CORAL

REEFS

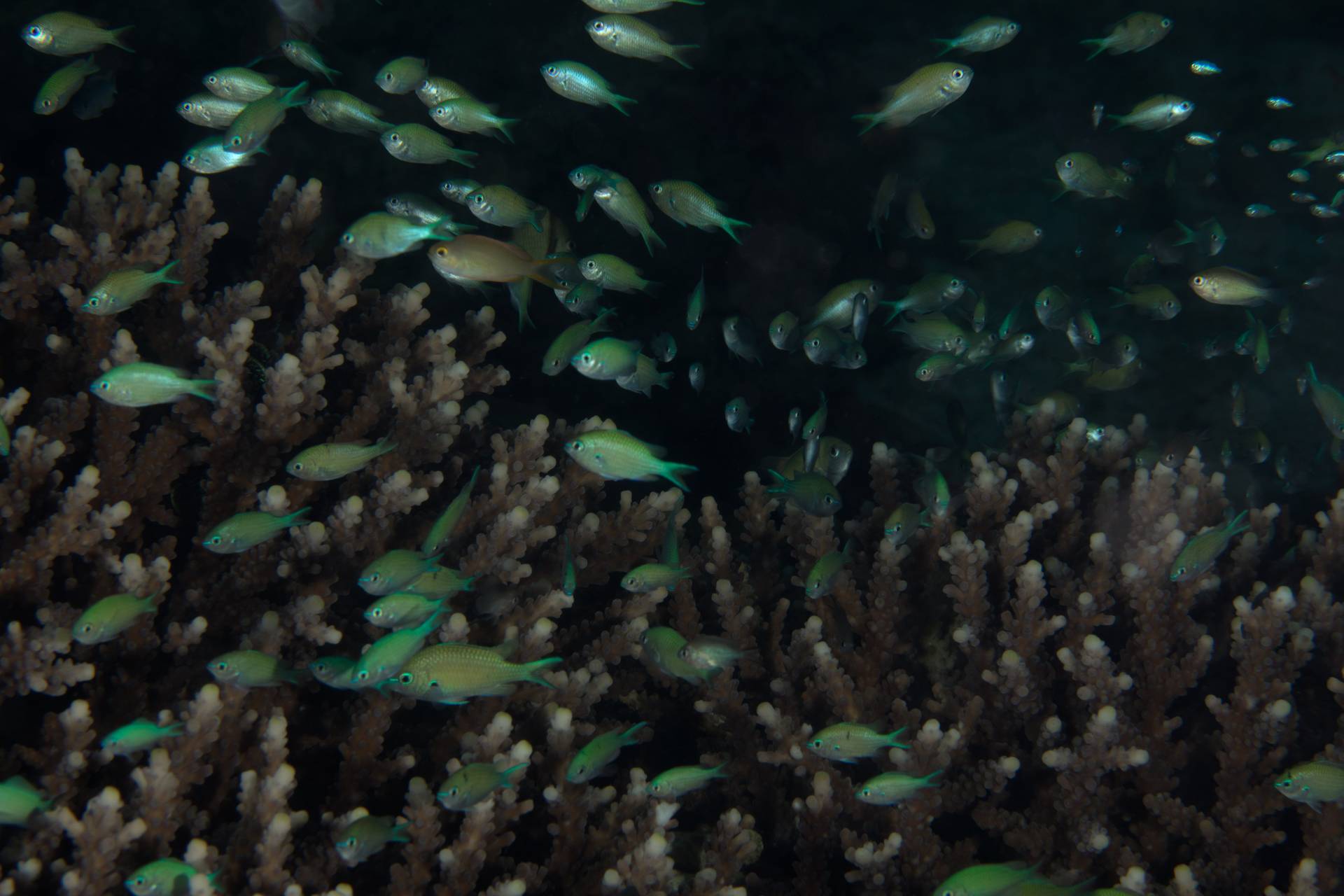

Occupying less than one percent of the world’s oceans (about half the size of France), coral reefs are home to more than one quarter of all marine species. Reefs themselves are made up of colonies of tiny invertebrate animals called corals, and they are home to countless tiny crustaceans, colorful sponges and vibrant fish. In films like Finding Nemo, coral reefs are portrayed as colorful, happy and healthy strongholds of marine life, but their very existence is threatened by warming waters, acidifying oceans and overfishing. In addition to providing homes for Dory (blue tang; Paracanthurus hepatus), Nemo (common clownfish; Amphiprion ocellaris) and thousands of other animals, reefs also protect coastlines, provide food and bring tourism. Unfortunately, the ability of reefs to provide these essential services is increasingly challenged. Protecting reefs from these dangers is critical because doing so safeguards the biodiversity, services and livelihoods that reefs sustain.

Some of the world’s highest reef biodiversity–the variety of life in a particular habitat–is found in Indonesia and the Philippines. Indonesia alone holds a staggering 17% of the world's total coral reefs. In both countries, millions of people are employed in fish-dependent industries. Unsurprisingly, these two nations lead the charge of aquarium fish exports globally. Of those coming into the United States (the world’s largest importer of aquarium fish), 56% come from the Philippines and 28% from Indonesia. These island nations export more Dories and Nemos than anywhere else. This is where the Reef to Aquarium expedition begins, in order to trace Dory back to her roots.

While a small number of fish like Nemo are easy to breed in captivity and can keep pace with aquarium demand, the same cannot be said for Dory. Blue tangs are pelagic spawners, they need an open ocean to lay their eggs directly into the water, which are then dispersed by currents and fertilized. Because of this life history, most Dory’s are wild-caught for direct import to the United States, or they are captured at a small size and raised in captivity until they reach their most marketable life stage. It is at this point that Dory–a young, brightly-colored and captivating reef fish–leaves her home and enters the first phase of the aquarium trade: collection. Currently, we don’t know whether wild blue tang populations can meet the demand of aquarists without endangering them. Nor do we know other ecological consequences of this global transaction.